In a recently published report, Stockholm Environment Institute researchers examined the difficulties CCAMLR has experienced in setting off large areas for marine protection (marine parks). They look into opportunities for multi-functional, adaptive marine spatial planning as a coming new reality.

The UN and member countries recently agreed to enact the “High Seas Treaty” housed under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In agreeing to the biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), nations are gearing up to protect the marine genetic resources in the vast areas of the open ocean beyond national EEZs (Exclusive Economic Zones) of 200 nautical miles. The central role that these marine ecosystems play with regard to biodiversity and carbon sequestration at a global scale make this agreement a cornerstone in humanity’s attempt at slowing the pace of species loss and global climate change.

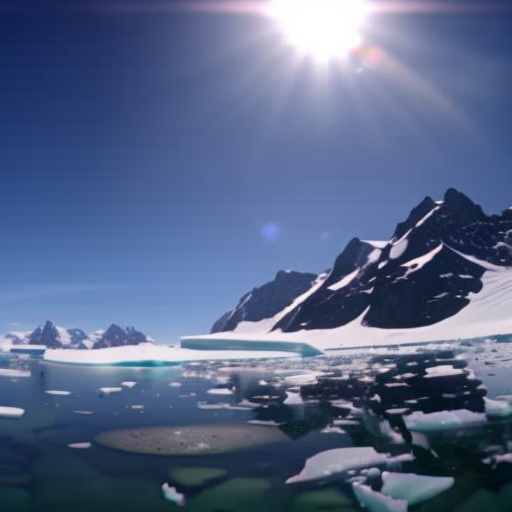

The implications of this global agreement and other marine spatial planning initiatives on the Antarctic and Southern Ocean – the most pristine and uninhabited region of the planet, currently managed by CCAMLR – remain unknown. The Commission’s primary objective has been conservation including rational use. CCAMLR has excelled at fisheries management with science- and ecosystem-based conservation measures at the centre of its strategy. The 27 member countries and 10 acceding states have successfully managed the major krill and finfish fisheries with extensive conservation measures and surveillance.

Fisheries management has, however, tended to overshadow other issues. The lack of consensus among member states on new marine protected areas (MPAs) is a cause for concern and may require alternative strategies for CCAMLR to achieve agreed-on conservation measures.

Other models attracting global attention include multilateral work such as the network of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSA) under the Convention on Biological Diversity. Marine spatial planning (MSP) described by UNESCO-IOC and the European Commission, the BBNJ and other approaches could contribute to the Antarctic Treaty System and are options for CCAMLR to consider.

The SEI report makes the following observations:

- The founding purpose of the Commission (CCAMLR) as a conservation regime with rational use of marine living resources is the basis for consensus-building among the member states. The nature of the organization should not be up for reinterpretation. CCAMLR, an integral part of the ATS, is a progressive conservation regime mandated to fulfil the objectives of the CAMLR Convention. Successful fishery management has been an outstanding legacy of CCAMLR and will always be a prominent part of its function and operation. Fishery management, however, should not overshadow the primary objective of the Convention, where regulating rational use is an integral part of the overall conservation mission. While there are different views on the nature of the organization, some are confused interpretations while others may be deliberate reinterpretation. Maintaining the clarity of CCAMLR as a conservation regime that includes rational use of marine living resources should reinforce the very foundation for consensus-building among member states.

- Science has been a defining feature of successful diplomacy in the Antarctic Treaty System. Science needs to continue to underpin policy options rather than be used for political gains. Science increases understanding and knowledge, leading to societal learning and adaptive management. Antarctic science is needed more than ever, not only as the foundation for governance and peaceful use of the Antarctic, but also because it is central to the conversation about the southern continent and its environment, including surrounding marine spaces, and because it is crucial for understanding global changes.

- As the last global frontier, the pristine state of the marine areas surrounding Antarctica provides an ideal natural laboratory to understand the impacts of climate change and human activities at large. Science is also instrumental for interstate cooperation and consensus-building.

- CCAMLR can retain its key role within the Antarctic Treaty System in area-based marine management by moving from the single focus on “MPA designation” towards a transformed common vision on “Southern Ocean” conservation and sustainability. High seas (i.e. marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, or ABNJ) represent 60% of the global ocean. Although 8% of the global ocean is protected in MPAs, only 1.2% of the high seas are protected, as noted by the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. It is hard to imagine a 30-by-30 target – protecting 30% of the planet’s land and sea area by 2030 – that can be realized without substantial increase of the protection of the high seas, marine areas surrounding Antarctica included. Here the Antarctic Treaty System and CCAMLR have been seen as global leaders and can continue to take a lead.

- While MPA designation seems to have reached a deadlock, the structure and function of the Commission remains solid. Following the principle of area-based management tools (ABMTs), including MPAs as fundamental for conservation of the global ocean, the specific proposals and designation need to be handled with pragmatism, collaboration and science diplomacy, as well as political solutions.

- Turn reputational risk into leadership opportunities, at a time of planetary crises and heightened geopolitical tensions. The CCAMLR and the Antarctic Treaty System are at a crossroads, inviting elements of transformation to respond to needs surrounding multifunctionality in marine spatial planning. These can be selectively applied under the banner of the Antarctic Treaty System to internationally available instruments.

The special meeting taking place June 19 – 23 in Santiago on MPAs provides an avenue for CCAMLR to strengthen its commitment to protect the marine living resources in Antarctica and agree on a road to the future.

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators in the Article

1. SDGs Addressed or Connected to the Issues Highlighted in the Article

- SDG 14: Life Below Water – The article discusses the need for marine protection and conservation measures in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean.

- SDG 15: Life on Land – The article mentions the importance of biodiversity and conservation efforts in the marine ecosystems of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean.

- SDG 13: Climate Action – The article highlights the role of marine ecosystems in carbon sequestration and their contribution to global climate change mitigation.

2. Specific Targets Under Those SDGs Based on the Article’s Content

- SDG 14.5: By 2020, conserve at least 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information.

- SDG 14.7: By 2030, increase the economic benefits to Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources, including through sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism.

- SDG 15.5: Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity, and protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species.

3. Indicators Mentioned or Implied in the Article to Measure Progress towards the Identified Targets

- Extent of marine protected areas (MPAs) established in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean.

- Economic benefits generated from sustainable use of marine resources in the region.

- Reduction in the degradation of natural habitats and halt in the loss of biodiversity in the marine ecosystems.

Table: SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | Target 14.5: By 2020, conserve at least 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information. | Extent of marine protected areas (MPAs) established in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean. |

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | Target 14.7: By 2030, increase the economic benefits to Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources, including through sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism. | Economic benefits generated from sustainable use of marine resources in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean. |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | Target 15.5: Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity, and protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species. | Reduction in the degradation of natural habitats and halt in the loss of biodiversity in the marine ecosystems. |

Behold! This splendid article springs forth from the wellspring of knowledge, shaped by a wondrous proprietary AI technology that delved into a vast ocean of data, illuminating the path towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Remember that all rights are reserved by SDG Investors LLC, empowering us to champion progress together.

Source: sei.org

Join us, as fellow seekers of change, on a transformative journey at https://sdgtalks.ai/welcome, where you can become a member and actively contribute to shaping a brighter future.