Study Design and Setting

In order to answer the research question, a novel DRR framework was first conceptualized. Next, the proposed framework was tested by applying it to the 2019 Cities100 report. This study followed a mixed methods design and was conducted between January 2022 and May 2022.

Study design and setting

The novel DRR framework was conceptualized following a grounded theory approach, which allowed for iterative and flexible qualitative data collection and analysis, fostering innovation throughout the process. Data collection at this phase stopped when the authors conceptualized an integrated DRR categorization.

Next, the novel integrated DRR framework was tested following a conceptual content analysis design. The transformative paradigm was used to answer the research question. Qualitative data was extracted from the 2019 Cities100 Report [32], whose data covers 58 cities spread globally. The report is released annually by C40 Cities Network, whose main funders are Bloomberg Philanthropies, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, and Realdania, a non-profit philanthropic association. The document was chosen because it systematically describes DRR interventions while other reports focused on a single intervention and they did not associate interventions to their multiple effects, such as socioeconomic consequences. Without seeing the association between interventions and potential socioeconomic consequences, the analysis would yield significantly skewed conclusions about the use of the framework across a range of DRR categories. Additionally, the 2019 Cities100 Report has a more diverse international focus compared to other similar reports, which are not as representative of the global population. Ensuring geographic variance increased trustworthiness and internal and external validity through reduced selection bias.

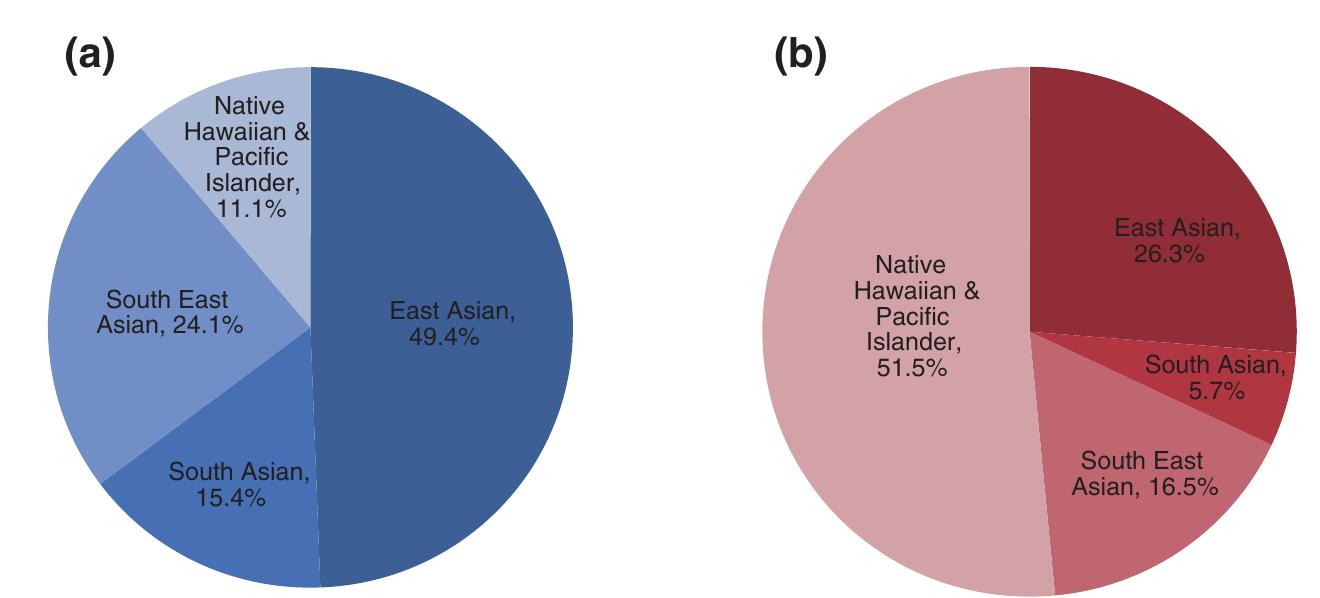

In 2019, the Cities100 report identified ongoing interventions implemented by each city, the unit of study in our research. Out of the 58 cities in the report, the authors manually selected 25 cities for this particular research question. Criterion purposeful sampling was used to select all of the cities that implemented interventions relevant to air pollution. The criteria for selection were the words “air” or “pollution”, or the presence of air pollution as a downstream effect of the intervention. The presence of a single criterion qualified the intervention to be selected. For instance, divesting away from fossil fuels would decrease air pollution even if the phrase “air pollution” was not specifically used. The selected cities are located in 15 countries, seven geographical regions, and span four income-level classifications.

The specific makeup of the chosen data set was analyzed using descriptive statistics to give insight into the distribution across geographical regions and income levels. Additionally, further descriptive statistics were used to show the distribution of DRR interventions across the proposed framework. The analysis was conducted in Sweden using Excel [33] by Mariya Dimitrova. Megan Snair verified data quality using iterative proofreading to ensure that the interventions from the 2019 Cities100 Report were categorized properly. The study complied with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guideline [34]. Establishing the novel integrated framework and its subcategories prior to data analysis was vital to ensuring data quality. Trustworthiness was enhanced through strengthened internal validity. For instance, the criteria within each DRR category, explained in the section “Creating a novel integrated framework to classifying DRR”, was clearly defined prior to data analysis. Additionally, pilot testing was conducted prior to data collection and analysis. Frequent monitoring of data collection and analysis by Megan Snair prevented duplicates, inconsistencies, analytical errors, and bias, including selection bias.

Creating a novel integrated framework to classifying DRR

The novel integrated framework (Table 1) cross tabulates two current classification frameworks, whose intersections are populated with examples to illustrate each type of DRR strategy.

- “Hazard, prospective” categories aim to prevent the hazard from occurring.

- “Hazard, corrective” categories attempt to mitigate current hazard risk.

- “Hazard, compensatory” interventions strive to increase the resilience solely to hazards.

In the second row, a DRR strategy that targets exposure aims to decrease how much or how often people or assets are in the way of hazards. Such interventions pre-emptively separate the hazard from people or assets, but they do not remove the hazard altogether. Moving across the row, “Exposure, prospective” occurs when an intervention attempts to prevent broad future exposure. “Exposure, corrective” categories attempt to reduce current exposure. “Exposure, compensatory” increase resilience to exposure.

Finally, the third row focuses on DRR strategies that target vulnerability of individuals or communities that are particularly susceptible to the effects of a disaster. Moving across the row, “Vulnerability, prospective” attempts to prevent the vulnerability from occurring. “Vulnerability, corrective” categories mitigate current vulnerability. “Vulnerability, compensatory” categories might be necessary when the vulnerability itself cannot be mitigated.

Testing the novel integrated approach to classifying DRR

First, data was extracted from the 2019 Cities100 report by creating a list of interventions for each city. Next, deductive conceptual content analysis was used to place/connect each public health intervention into the DRR categories of the proposed DRR framework from Table 1. Each connection was given a value of one for the continuous data set. A dichotomous data set was also created, where each city received a value of one if the city used a DRR category at least once. The resulting percentage accounts for the over-representations of certain regions and income levels because it considers the total number of possible DRR connections from the proposed DRR framework, and not just the sum number of connections presented in the 2019 Cities100 Report.

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- SDG 13: Climate Action

- SDG 15: Life on Land

The article discusses disaster risk reduction (DRR) interventions in cities, specifically focusing on air pollution. These interventions are directly related to SDG 11, which aims to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Additionally, addressing air pollution is crucial for achieving SDG 13, which focuses on taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. Furthermore, the article mentions increasing green spaces as a compensatory action to increase resilience to air pollution, which is connected to SDG 15, which aims to protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

- SDG 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management.

- SDG 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning.

- SDG 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services.

The article emphasizes the need to address air pollution in cities, which aligns with SDG 11.6. This target specifically focuses on reducing the adverse environmental impact of cities, including air quality. Additionally, integrating climate change measures into policies and planning is essential, as stated in SDG 13.2. Finally, the article mentions increasing green spaces as a compensatory action to increase resilience to air pollution, which relates to the conservation and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems mentioned in SDG 15.1.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Air pollution levels (e.g., particulate matter concentrations, nitrogen dioxide levels) can be used as indicators to measure progress towards SDG 11.6.

- The integration of climate change measures into policies and planning can be assessed through indicators such as the inclusion of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies in urban development plans.

- Indicators related to the conservation and restoration of terrestrial ecosystems can include the percentage of urban areas covered by green spaces, the increase in urban tree canopy cover, and the preservation of biodiversity within cities.

The article does not explicitly mention specific indicators. However, air pollution levels, such as particulate matter concentrations and nitrogen dioxide levels, can be used to measure progress towards SDG 11.6. The integration of climate change measures into policies and planning can be assessed by examining the inclusion of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies in urban development plans. Indicators related to the conservation and restoration of terrestrial ecosystems can include the percentage of urban areas covered by green spaces, the increase in urban tree canopy cover, and the preservation of biodiversity within cities.

Table: SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management. | – Air pollution levels (e.g., particulate matter concentrations, nitrogen dioxide levels) – Inclusion of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies in urban development plans – Percentage of urban areas covered by green spaces – Increase in urban tree canopy cover – Preservation of biodiversity within cities |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning. | – Inclusion of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies in urban development plans |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services. | – Percentage of urban areas covered by green spaces – Increase in urban tree canopy cover – Preservation of biodiversity within cities |

Copyright: Dive into this article, curated with care by SDG Investors Inc. Our advanced AI technology searches through vast amounts of data to spotlight how we are all moving forward with the Sustainable Development Goals. While we own the rights to this content, we invite you to share it to help spread knowledge and spark action on the SDGs.

Fuente: globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com

Join us, as fellow seekers of change, on a transformative journey at https://sdgtalks.ai/welcome, where you can become a member and actively contribute to shaping a brighter future.