Enhancing Adaptive Social Protection through Climate Risk Financing: A Strategy for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Climate Shocks and the Imperative for Adaptive Social Protection

The increasing frequency and intensity of natural hazards and climate-related risks present significant challenges to social protection systems, particularly in low- and middle-income nations. This trend directly threatens progress towards key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). In response, governments are developing adaptive social protection (ASP) systems, which are integrated frameworks designed to protect poor and vulnerable populations from shocks. The efficacy of these systems is contingent upon robust and timely financing, especially during crises when social protection budgets must be scaled up to deliver rapid relief.

Financing Mechanisms for Shock-Responsive Social Protection

Governments face critical decisions regarding the financing of ASP systems during disasters. Traditional post-disaster funding mechanisms often carry risks that can undermine long-term sustainable development.

- Post-Disaster Funding Options: These include reallocating funds from other budget lines, heavy borrowing, or seeking ad hoc humanitarian aid from international partners.

- Associated Risks: Such measures can lead to fiscal instability, increased national debt, and a dependency on donors, compromising national efforts towards achieving the SDGs.

Pre-arranged financing offers a more strategic approach to scaling up funding for shock-responsive social protection, aligning with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by fostering proactive financial planning.

- Contingency Funds: Government reserve funds, functioning like savings accounts, can be established based on historical loss data.

- Risk Transfer Instruments: Tools like climate risk insurance, sovereign contingency loans, and catastrophe bonds provide access to capital when pre-agreed disaster triggers are met.

Climate Risk Insurance as a Tool for SDG Attainment

Climate risk insurance is an increasingly utilized instrument for pre-arranged disaster financing. Governments pay annual premiums to an insurance provider and receive a payout following a qualifying disaster. This mechanism directly supports several SDGs:

- SDG 2 (Zero Hunger): In 2024, the government of Zimbabwe received a $16.8 million payout from the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group following a drought-induced failed agricultural season, demonstrating how insurance can mitigate severe food insecurity.

- SDG 13 (Climate Action): By providing a financial buffer against climate shocks, insurance strengthens national resilience and adaptive capacity (Target 13.1).

However, the effectiveness of this tool is subject to certain conditions. Premiums can be costly, and the impact of a payout is entirely dependent on the efficiency of the delivery systems in place. Recognizing this, a recent UN Development Programme (UNDP) report emphasizes the importance of integrating risk finance with strengthened social protection delivery systems to ensure that funds reach those most in need, a key aspect of achieving SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Payout and Delivery Systems: Ensuring Impact for Vulnerable Populations

The design of insurance payout mechanisms is critical for determining the speed and reliability of fund distribution to affected populations. Two primary models exist:

- Direct Payouts: The beneficiary receives funds directly from the insurance provider.

- Indirect Payouts: The provider transfers the payment to an intermediary, such as a government agency or mobile banking provider, which then manages distribution to the final recipients.

The ideal approach involves “piggybacking” insurance payouts onto existing government-run social protection programs. This leverages established infrastructure to deliver cash transfers, food assistance, and other recovery aid quickly and efficiently. While this strategy holds great promise for advancing SDG 1 (No Poverty) by preventing households from falling into poverty due to shocks, its implementation is often complex and rarely seamless.

Conclusion: From Short-Term Relief to Long-Term Resilience

Pre-arranged financing instruments, including climate risk insurance and catastrophe bonds, are vital tools for bridging fiscal gaps when disasters strike. By channeling funds through adaptive social protection systems, they ensure that relief reaches the most vulnerable populations. A crucial question remains regarding their long-term impact: do these mechanisms merely fill short-term funding gaps, or do they contribute to sustainable poverty reduction and build long-term resilience, in line with SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities)? The integration of these financial instruments with robust, well-functioning ASP systems is essential for transforming reactive relief efforts into a proactive strategy for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

SDGs Addressed in the Article

Detailed Analysis

-

SDG 1: No Poverty

- The article’s central theme is the implementation and funding of “adaptive social protection (ASP) systems” designed to “cushion poor and vulnerable groups against shocks.” This directly addresses the goal of ending poverty by creating systems that prevent people from falling into poverty due to disasters and climate events. The text questions whether these financial mechanisms “drive sustainable poverty reduction and resilience.”

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

- The article explicitly connects climate shocks to food security. It cites the example of Zimbabwe receiving a payout from the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group after a “failed agricultural season and severe food insecurity following drought.” This highlights the link between disaster response financing and preventing hunger.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

- The article is framed around the challenge of “natural hazards and climate risks” that are increasing in “intensity and frequency.” It discusses tools like “climate risk insurance” and other forms of “pre-arranged financing” as mechanisms for governments to strengthen resilience and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- The article mentions multiple actors working together to address these challenges. This includes governments, “international partners” providing humanitarian aid, regional insurance providers like the “African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group,” and UN agencies like the “UN Development Programme (UNDP),” which commissioned guidance on integrating risk finance. This demonstrates the multi-stakeholder partnerships needed to mobilize financial resources.

Specific Targets Identified

Detailed Analysis

-

Target 1.3: Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all… and achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable.

- The article is entirely focused on “social protection systems” and making them “adaptive” and “shock-sensitive.” It discusses the need to “scale up social protection budgets” and leverage “existing social protection programmes” to deliver relief, which directly aligns with implementing and expanding these systems.

-

Target 1.5: Build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters.

- This target is the core concept of the article. The text describes “adaptive social protection (ASP) systems” as a direct response to increasing climate risks. The use of “pre-arranged financing” and “climate risk insurance” are presented as tools to build the financial resilience of governments and, by extension, the poor and vulnerable populations they serve.

-

Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.

- The article discusses how governments can strengthen their ability to respond to disasters through financial planning. Mechanisms like “contingency budget lines,” “government reserve funds,” and “climate risk insurance” are all strategies to enhance a country’s adaptive capacity to manage the financial fallout from climate-related hazards.

-

Target 17.3: Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources.

- The article details various financial instruments beyond traditional government budgets. It discusses seeking “ad hoc humanitarian aid from international partners” and using market-based tools like “climate risk insurance,” “sovereign contingency loans and catastrophe bonds (cat bonds)” to bridge fiscal gaps, which are all forms of mobilizing financial resources from multiple sources.

Indicators for Measuring Progress

Detailed Analysis

-

Mentioned: Amount of financial resources provided for disaster response.

- The article provides a concrete example of this indicator: “the government of Zimbabwe received a $ 16.8 million payout from the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group.” This figure is a direct measure of the financial resources mobilized and disbursed through a climate risk insurance mechanism to address a specific crisis.

-

Implied: Proportion of the population covered by social protection systems.

- The article discusses the challenge of ensuring that insurance payouts and other relief funds “reach those who need it most.” The effectiveness of these systems is tied to their ability to cover the intended beneficiaries. Therefore, the percentage of the poor and vulnerable population covered by these systems is a critical, though not explicitly stated, indicator of success.

-

Implied: Existence of national strategies for disaster risk financing.

- The article describes a range of strategic options for governments, such as establishing “contingency budget lines,” “government reserve funds,” and arranging complex financial instruments like “catastrophe bonds.” The adoption of these “pre-arranged financing” mechanisms by a government serves as an indicator that it has a formal strategy in place for financing disaster response.

Summary Table: SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 1: No Poverty | 1.3: Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems. 1.5: Build the resilience of the poor to climate-related extreme events. |

Implied: Proportion of the population covered by social protection systems. |

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | 2.1: End hunger and ensure access to food for all, especially the vulnerable. | Implied: Reduction in severe food insecurity following a disaster. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards. | Implied: Existence of national strategies for disaster risk financing (e.g., contingency funds, insurance). |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.3: Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources. | Mentioned: Amount of financial resources provided for disaster response (e.g., “$ 16.8 million payout”). |

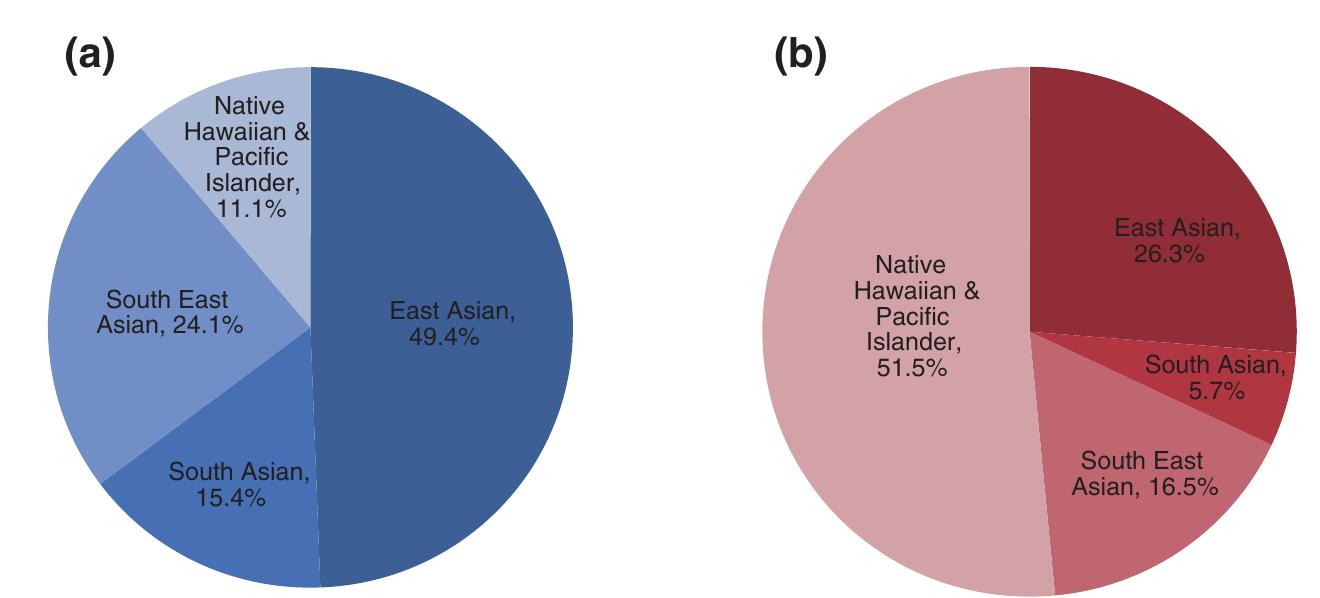

Source: risingnepaldaily.com