Report on the Link Between Air Pollution and Dementia Risk in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals

Executive Summary

A comprehensive global analysis reveals a significant correlation between exposure to common air pollutants and an increased risk of dementia. This finding has profound implications for public health strategies and the achievement of several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), most notably SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The research underscores the urgent need for integrated policy interventions across environmental, transport, and urban planning sectors to mitigate this growing health crisis.

Analysis of Findings

A meta-analysis of 51 international studies, covering nearly 30 million individuals, establishes a clear link between long-term exposure to air pollution and the onset of dementia. The global prevalence of dementia, currently affecting over 57 million people, is projected to nearly triple by 2050, posing a significant challenge to the targets of SDG 3.

Identified Pollutants and Quantified Risks

The investigation focused on three primary pollutants largely originating from industrial and transport activities, which are key areas of concern for SDG 11.

- Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5): Sourced from vehicle exhaust, industry, and construction. A 10 µg/m³ increase in exposure is associated with a 17% rise in dementia risk.

- Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂): Primarily from fossil fuel combustion in vehicles. A 10 µg/m³ increase is linked to a 3% rise in dementia risk.

- Soot (Black Carbon): Generated by diesel exhaust and wood fires. A 1 µg/m³ increase is associated with a 13% rise in dementia risk.

Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

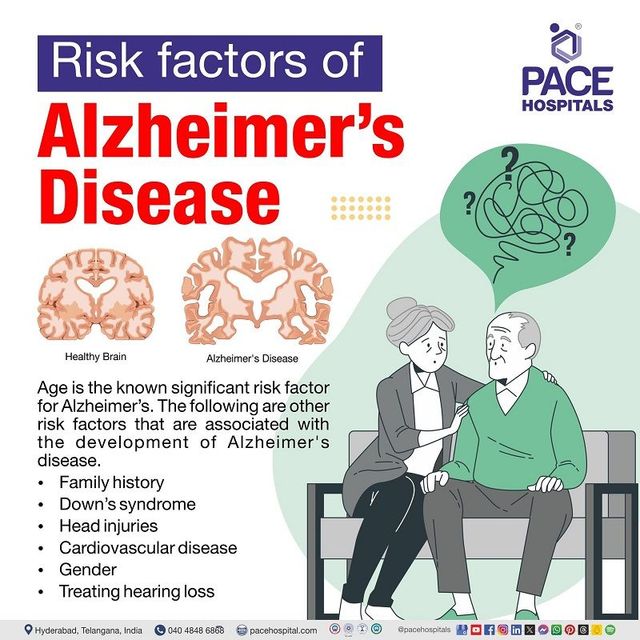

The findings directly impact SDG Target 3.4, which aims to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases. Air pollution is identified as a critical environmental risk factor for dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

- Mechanism of Harm: Pollutants are believed to induce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, either through direct entry or indirectly via the circulatory system. These processes are known contributors to neurodegeneration.

- Healthcare Burden: By exacerbating dementia rates, air pollution increases the strain on healthcare systems, families, and caregivers, undermining efforts to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The report highlights that urban environments are epicenters of this health risk, directly challenging SDG Target 11.6, which calls for reducing the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including air quality.

- Urban Pollution Levels: In 2023, Central London’s average roadside PM2.5 level was 10 µg/m³, the exact concentration linked to a 17% higher dementia risk.

- Policy Integration: The research validates the need for urban planning, transport policy, and environmental regulation to be integrated with public health objectives. Preventing dementia is not solely a healthcare responsibility but a key outcome of creating sustainable and healthy cities.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

A significant equity gap was identified in the existing body of research, a direct concern for SDG 10, which aims to reduce inequality within and among countries.

- Research Bias: The majority of studies were conducted in high-income nations with predominantly white populations.

- Disproportionate Impact: Marginalized communities, which often experience higher levels of pollution exposure, are critically underrepresented in research. This gap hinders the development of equitable policies to protect the most vulnerable populations.

Recommendations for Interdisciplinary Action (SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals)

Achieving a reduction in the dementia burden requires a multi-sectoral approach, embodying the spirit of SDG 17. The evidence supports a clear mandate for collaboration between health authorities, environmental agencies, and urban planners.

Key Policy Interventions

- Enact Stricter Regulations: Implement more stringent air quality standards for key pollutants, targeting major contributors such as the transport and industrial sectors.

- Promote Sustainable Urban Design: Prioritize urban and transport planning that reduces reliance on polluting vehicles and promotes cleaner air.

- Foster Equitable Research: Direct funding and effort towards studying the impacts of air pollution on diverse and marginalized populations to ensure equitable health outcomes.

In conclusion, addressing air pollution is a critical and effective strategy for protecting global brain health and advancing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The co-benefits of such actions include improved public health, greater social equity, and enhanced climate resilience.

SDGs Addressed in the Article

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- The article’s central theme is the link between air pollution and the increased risk of dementia, a significant health issue. It discusses how pollutants like PM2.5, NO₂, and soot contribute to non-communicable diseases (dementia), affecting the well-being of millions globally. The text highlights the burden on patients, families, and healthcare systems, directly aligning with the goal of ensuring healthy lives.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- The article explicitly connects air pollution to urban environments. It mentions that pollutants are generated by “vehicle exhaust, industrial processes, wood burning, and construction dust,” all common in cities. It provides specific data for air pollution levels in cities like London, Birmingham, and Glasgow. Furthermore, it calls for solutions in “urban design, environmental policy, and transportation planning,” which are core components of creating sustainable cities.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- The article points out an “equity gap in air pollution studies,” noting that “marginalized communities often face higher exposure to pollution, yet they remain underrepresented in research.” This highlights an inequality in both health outcomes and research focus, connecting to the goal of reducing inequalities within and among countries. The call for equitable policy interventions reinforces this link.

Identified SDG Targets

-

Target 3.4: Reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases

- The article focuses on dementia, a non-communicable disease. By establishing a clear link between air pollution and an increased risk of dementia, it underscores the importance of prevention. The call to tackle air pollution is presented as a preventive measure to “reduce the immense burden on patients, families, and caregivers,” which aligns with reducing the impact of non-communicable diseases.

-

Target 3.9: Substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination

- This target is directly addressed. The article provides evidence that long-term exposure to air pollutants (PM2.5, NO₂, soot) is a “risk factor for the onset of dementia.” It quantifies this risk, thereby identifying air pollution as a direct cause of illness.

-

Target 11.6: Reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality

- The article’s focus on air quality in urban centers is a direct reflection of this target. It discusses pollutants primarily found in cities and provides specific measurements for “roadside PM2.5 level in Central London” and NO₂ levels. The recommendation for interventions in “urban planning, transport policy, and environmental regulation” aims to reduce the adverse environmental impact of cities, specifically concerning air quality.

Implied or Mentioned Indicators

-

Indicator 3.9.1: Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution

- While the article discusses morbidity (illness) more than mortality (death), it provides quantifiable data on the health risks associated with ambient air pollution. It states, “for every 10 micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m³) increase in PM2.5, the relative risk of developing dementia rose by 17 percent.” This quantifies the health burden of air pollution, which is the basis for this indicator.

-

Indicator 11.6.2: Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5 and PM10) in cities

- The article explicitly mentions and uses this indicator. It reports that “in 2023, the average roadside PM2.5 level in Central London was 10 μg/m³.” It also provides data for NO₂ and soot levels in London, Birmingham, and Glasgow. These are direct measurements used to track progress on urban air quality.

Summary of Findings

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.4: By 2030, reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment.

3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. |

3.9.1 (Implied): The article quantifies the increased risk of dementia (a non-communicable disease) from specific levels of air pollutants, such as a 17% rise in dementia risk for every 10 μg/m³ increase in PM2.5. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. | 11.6.2 (Mentioned): The article cites specific annual mean levels of pollutants in cities, stating “the average roadside PM2.5 level in Central London was 10 μg/m³” and London’s average NO₂ level was “33 μg/m³.” |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | The article highlights an “equity gap” where marginalized communities face higher pollution exposure but are underrepresented in research, aligning with the overall goal of reducing health and research inequalities. | No specific quantitative indicators are mentioned in the article for this goal, but the qualitative issue of the “equity gap” is identified. |

Source: earth.com