Report on U.S. PFAS Drinking Water Regulations and Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

1.0 Executive Summary

A recent legal challenge has prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to reconsider aspects of its National Primary Drinking Water Regulation for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The agency’s motion to vacate regulations for four of the six targeted chemicals raises significant concerns regarding the nation’s progress toward key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). This report outlines the regulatory developments, stakeholder responses, and the direct impact on established global sustainability targets.

2.0 Regulatory and Legal Context

The EPA’s actions stem from a lawsuit filed by water utility associations, which alleged procedural failures in the establishment of the 2024 drinking water standards.

- Litigation Origin: The American Water Works Association (AWWA) and the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies (AMWA) sued the EPA, claiming the agency did not follow the required processes under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

- EPA’s Concession: The EPA has filed a motion for a partial vacatur, agreeing with the plaintiffs that a required public comment period was not held for four specific PFAS compounds.

- Regulatory Division: The EPA’s legal strategy now differentiates between two groups of PFAS chemicals.

- Regulations to be Vacated: The agency seeks to rescind standards for PFHxS, PFNA, PFBS, and HFPO-DA (GenX), citing procedural flaws. This action compromises the comprehensive management of chemical waste, a key component of SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

- Regulations to be Defended: The EPA will continue to defend its legally enforceable limits for PFOA and PFOS, the two most well-known PFAS compounds.

3.0 Impact on Sustainable Development Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

The partial reversal of the PFAS regulation directly impedes progress toward SDG Target 6.1, which aims to achieve universal access to safe and affordable drinking water. The weakening of these standards represents a significant setback for ensuring water quality for all citizens.

- Reduced Scope of Protection: By removing four PFAS chemicals from the regulation, the EPA narrows the definition of “safe” drinking water, potentially leaving populations exposed to harmful contaminants.

- Delayed Compliance: The EPA plans to extend the compliance timeline for the remaining PFOA and PFOS regulations from 2029 to 2031. This delay postpones the realization of safer drinking water, further hindering the achievement of SDG 6.

- Industry Implications: The uncertainty affects leachate management and groundwater monitoring for the waste industry, complicating efforts to ensure environmentally sound management of chemicals as stipulated in SDG 12.4.

4.0 Implications for Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being

The decision to roll back drinking water protections has direct consequences for public health, challenging the objectives of SDG Target 3.9, which seeks to substantially reduce illnesses and deaths from hazardous chemicals and water pollution.

- Public Health Risks: Environmental and health advocacy groups, including Earthjustice and the Natural Resources Defense Council, argue that the EPA’s action will prolong the exposure of millions of Americans to toxic “forever chemicals” linked to severe health issues.

- Institutional Accountability: Critics contend the EPA is attempting to weaken established standards in a manner that bypasses provisions in the Safe Drinking Water Act designed to prevent such reversals, raising questions about institutional integrity under SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

5.0 Legislative and Stakeholder Responses

The EPA’s move has elicited strong reactions from various stakeholders, highlighting the multi-faceted challenge of achieving sustainability goals, as referenced in SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

5.1 Environmental Advocacy

- Environmental groups have condemned the EPA’s motion, framing it as an attempt to evade its congressional mandate to protect public health from known chemical threats.

5.2 Legislative Action

- In response to the regulatory uncertainty, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced the PFAS National Drinking Water Standard Act of 2025.

- The bill’s stated purpose is to codify the original, more comprehensive PFAS standards set by the Biden administration, thereby making them durable and insulated from future administrative reversal. This legislative effort represents a partnership to uphold and advance public health and environmental protection goals.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

- The entire article revolves around the regulation of drinking water quality. It discusses the U.S. EPA’s “National Primary Drinking Water Regulation” and the establishment of “legally enforceable limits for six types of PFAS in drinking water.” This directly addresses the core mission of SDG 6, which is to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all, with a key focus on water safety.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- The primary motivation for regulating PFAS chemicals is to protect public health. The article mentions that a rollback of the standard would “weaken the ability to protect residents from exposure to the chemicals” and references criticism from groups concerned about keeping millions “exposed to toxic forever chemicals in tap water.” This aligns with SDG 3’s goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being, specifically by reducing illnesses from water contamination.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- The article details a legal and institutional conflict involving the EPA, water utility associations, and the court system. The lawsuit centers on whether the EPA “did not follow required legal steps under the Safe Drinking Water Act.” The EPA’s admission that it “denied the public and the regulated community the opportunity to adequately comment” highlights issues of institutional accountability, transparency, and participatory decision-making, which are central to SDG 16. The introduction of the “PFAS National Drinking Water Standard Act of 2025” also reflects efforts to create durable and effective institutional frameworks.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

- The problem of PFAS contamination originates from the production and use of these chemicals. The article discusses the need for regulations to manage these “toxic forever chemicals.” This connects to SDG 12’s aim to achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and wastes throughout their life cycle to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 6.1: Achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.

- The establishment of a “National Primary Drinking Water Regulation” with “legally enforceable limits” for PFAS is a direct policy action aimed at ensuring that drinking water supplied by utilities is safe for consumption, which is the essence of this target.

-

Target 3.9: Substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.

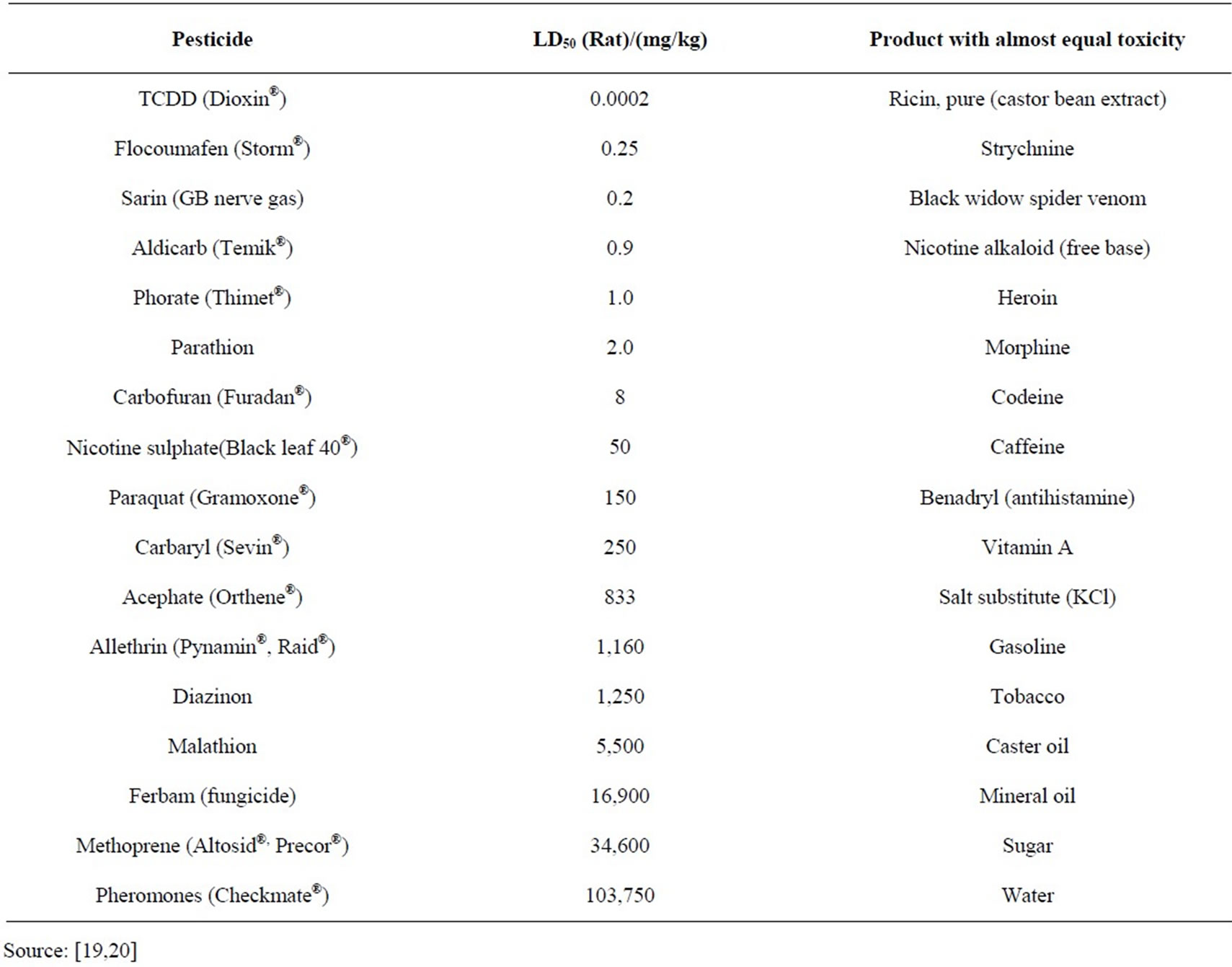

- The regulation is designed to limit public exposure to hazardous PFAS chemicals (PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFBS, and GenX) through drinking water, thereby directly addressing the goal of reducing illnesses caused by water contamination.

-

Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

- The lawsuit filed by water associations challenges the EPA’s process, alleging it “did not use the best available data and appropriate processes.” The EPA’s subsequent motion to vacate parts of its own rule because it failed to provide a “required public comment period” is a clear example of institutional accountability mechanisms at work.

-

Target 12.4: Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle.

- By setting standards for PFAS in drinking water, the regulation indirectly pressures industries to better manage these chemicals. The article notes the waste industry is “closely following how these drinking water rules could affect leachate management and groundwater monitoring efforts,” indicating a direct link to the management of chemical waste.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

- An implied indicator is the existence and enforcement of national regulations for drinking water quality. The article is centered on the “National Primary Drinking Water Regulation” and the proposed “PFAS National Drinking Water Standard Act of 2025.” The status of these regulations (proposed, finalized, rolled back, or codified into law) serves as a direct measure of progress.

-

Concentration of Pollutants in Drinking Water

- The article names specific pollutants to be regulated: “PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFBS and HFPO-DA.” The “legally enforceable limits” for these chemicals are a key indicator. Measuring the concentration of these specific PFAS types in public water systems against these limits would be a direct way to track progress toward safe drinking water (Target 6.1) and reduced exposure to hazardous chemicals (Target 3.9).

-

Public Participation in Decision-Making

- The legal challenge hinges on the lack of a “required public comment period.” The adherence to such procedural requirements for public participation in the rulemaking process is an indicator of institutional transparency and responsiveness (Target 16.6). The lawsuit itself and the EPA’s response serve as evidence of this indicator being actively monitored by civil society and industry groups.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs, Targets and Indicators | Corresponding Targets | Specific Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation | 6.1: Achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all. | Establishment and enforcement of the “National Primary Drinking Water Regulation” for PFAS. |

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.9: Substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and water pollution. | The setting of “legally enforceable limits” for specific toxic chemicals (PFOA, PFOS, etc.) in drinking water to reduce public exposure. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. | Adherence to procedural requirements like the “required public comment period” under the Safe Drinking Water Act; use of legal challenges to hold institutions accountable. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.4: Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes. | Regulations affecting “leachate management and groundwater monitoring,” indicating improved management of chemical waste streams. |

Source: wastedive.com